Writers can have an impact that can spill over to more than just their readership. When a writer can research a subject and flesh out his findings in an easy-to-read format, he can bring awareness to an issue and spread thoughts to a broad audience without access to that information.

When it comes to alerting the world about the potential for viral spillover – the process by which an animal virus infects a human – few have done as much to raise awareness as has author David Quammen.

( Image courtesy of Oregon State University at Wikimedia Commons)

How did he do this? What contributions has he made to the world of emerging viral threats? Are his warnings timely?

Read on; like David Quammen, you may be surprised by what you discover.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

-

01

No Stranger to Writing

-

02

The Concept of Spillover

-

03

How Does Spillover Happen?

-

04

David Quammen’s Warning?

-

05

What Can We Do?

-

06

What Can You Do?

-

07

Frequently Asked Questions

No Stranger to Writing

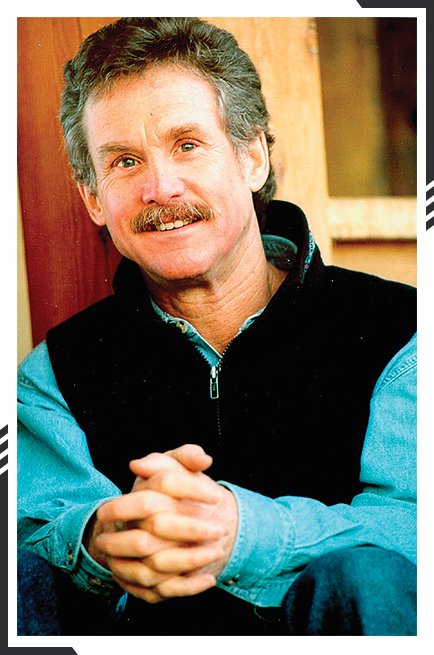

Often, what is found is that somebody who writes a book has another job that serves as their primary income stream. When it comes to David Quammen, though, writing is what he knows, and it's what he does full-time.

He's long contributed to Rolling Stone, National Geographic, Outside magazine, Esquire, Harper's, Powder, and the New York Times, mainly as a science writer in each role. Not only having an active interest in all things outdoorsy, but David Quammen is also a prolific traveler, spending a lot of time on a plane and in the jungles to research the world around him.

On one of these journeys, David Quammen participated in a conversation that was soon to not only give him direction with the next step writing-wise but also assist in opening the world's eyes to the dangers of animal viruses potentially causing the next human pandemic.

In 2006, Quammen was sitting by a campfire deep in the heart of Africa, listening to the talk around him. The silence of the night, combined with the glow of embers, causes men to become talkative, and two African men across from him discuss the time that Ebola had rampaged their village.

( Image courtesy of CDC Global atWikimedia Commons)

The horrors they detailed were disturbing, to say the least, but it was one particular factoid they glossed over that burned itself into Quammen's mind. One of the men mentioned how, as they walked through the jungle near their village one day, they came across a massive pile of 13 dead gorillas.

Questions immediately began to bubble up.

Why were gorillas dying in an Ebola outbreak? Do gorillas get Ebola as well? Is this something that both man and primate can get? And was it possible…did the gorillas give the villagers Ebola?

Ebola outbreak, 2000 ( Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

These thoughts haunted David Quammen for the next six years. And it was when National Geographic contracted him for an article on zoonotic diseases that he got the chance to finally seek out the answers he had hoped for so long. He was going to investigate spillover.

A short article titled "Deadly Contract" was written in 2007, but as is often the case, an article can prove to be nothing more than the seed from which a book is borne. A book contract soon followed, and so began Quammen's quest to learn more about how animals could give viruses to humans. And given humanity's past fighting off diseases, what did this mean for the future?

To get his answers, Quammen spent roughly five years traveling the globe, talking with professionals in the various fields associated with virology anywhere he could. He traveled throughout the Congo to get more information about Ebola. He went to China to learn more about bat-borne viruses. Bangladesh, New York City, and high-security bio-labs became his favorite haunts. He spent time in each of these locations, taking his questions with him and, hopefully, leaving with nothing but answers.

( Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The result was a book that would soon become a New York Times Bestseller, win The Science and Society Book Award, and be granted the Society of Biology Book Award in the United Kingdom. People want to know why spillover can happen.

The Concept of Spillover

We live in a world where things can get sick. Viruses, bacteria, and parasites are everywhere in the world around us, and they're even living in you right now. It's currently estimated that 95% of the earth's population is infected with a parasite of some sort. But could some of these illnesses that humanity faces regularly come from animals?

Absolutely.

This is the concept of Spillover.

Some diseases are what scientists call zoonoses – viruses that can jump from an animal to infect a human being.

( Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Several variables are at play regarding what viruses can make the leap. Still, when they do, the possibility that they can very quickly have pandemic potential is astounding. Picture, if you will, a seasoned US soldier. He's seen battles in Afghanistan and Iraq, so he knows a thing or two about combat. But then, one day, he is sent to fight against an enemy he has never seen before. They utilize weaponry he's entirely dumbfounded by. Their tactics are 100% original. He doesn't know what to do – at a loss for how to respond. Every action he takes seems insignificant if it doesn't aggravate the whole process.

Isn't this the premise behind every alien invasion movie?

In a way, this is how the immune system is when it comes to fighting zoonosis. If it's a new virus to humanity, everything about it is unique. Nobody has ever had to have their immune system fight this thing off before, and as a result, the virus can spend a significant amount of time wreaking havoc before it can finally be stopped.

This is the danger of spillover.

Quammen sought to highlight how this would play out through his book and what he found was concerning. Finally publishing his book Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic in 2013, David's research led him to believe that what he referred to as the NBO, or Next Big One, would be a virus that came from an animal.

( Image courtesy of Peiron59 atWikimedia Commons)

How did he come to this conclusion?

Simple. He looked at the facts.

Every year, there are over one billion cases of zoonotic diseases globally. This means that one billion people per year become sick with something they have caught from an animal. Annually, this costs the world hundreds of billions of dollars in economic loss. In other words, humans getting sick from animals is nothing new.

What is new, however, is that the spillover rate is speeding up more than we've ever witnessed before. For example, of all the disease-causing pathogens known to man, only about 15% are spillover viruses. But if you look at all of the viruses that have been discovered since 1980? Then you'll find that 65% of what we've learned within that time frame are zoonoses.

But it's not just that we're discovering new zoonoses. We're seeing them impact humanity more and more as well.

Stay Away from the Bat…Man.

Bats are one of the most common causes of spillover viruses in human beings. In fact, they have the potential to carry more zoonoses than any other animal on the planet that we know of as of yet, meaning that the probability of a bat vector with any novel infectious disease is incredibly high. Marburg, Nipah, SARS coronavirus, and Hendra are all high-fatality spillover viruses from bats. Others are also suspected of originating from these flying mice, such as Ebola and MERS coronavirus.

Recent history has confirmed this as well. If we look back at the 2003-2004 SARS-CoV epidemic, it was conclusively traced back to bats in Southern China. It's hard to argue against the fact that horseshoe bats in the region were found with SARS-CoV, which was 98% genomically similar to the human strain.

( Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The same goes for the 2002 swine acute diarrhea syndrome (SADS) outbreak. This, too, was traced back to Chinese bats flying nearby swine farms. If you remember, this was the premise behind the excellent Matt Damon movie Contagion.

The Nipah outbreak in Bangladesh and India had a 70-90% mortality rate? That was from bats.

The Nipah that hit the Philippines and the Hendra virus that hit Australia with 60-80% mortality? That came from horses – who got sick from bats.

What about the Nipah outbreak in Malaysia and Singapore that caused 40% mortality? Again, bats.

( Image courtesy of Paramanu Sarkar atWikimedia Commons)

You get the point.

Bats can make people sick. But the issue is that we see signs of this happening more often.

We must look no further than the Hendra virus to see this truth exhibited.

Hendra is a particularly nasty virus that can easily lead to death. It's endemic to Australia and carried by Australian fruit bats. What tends to happen is that bats will roost in stables where horses live, poop everywhere, and somehow, the horses will come into contact with this guano (bat poop). Maybe the poop lands in the horse's water. Maybe the horse breathes aerosolized dried guano. Perhaps the horse eats a bit of hay with guano on it. Regardless of the route, somehow, that horse ends up with a virus that a bat shed.

Australian woman holding a fruit bat. ( Image courtesy of Mike’s Birds at Wikimedia Commons)

Next, the horse amplifies the virus and can give Hendra to their human handlers.

A NOTE OF INTEREST

While domestic and wild animals can cause spillover events, wild animals tend to cause more severe zoonoses.

From 1995-2005, cases of Hendra virus spillover within Australia were sporadic. There would be isolated incidents here and there, alarming, of course, but it was never associated with any outbreak. Then, in 2006, that all seemed to change. All of a sudden, there were associations between cases.

What made the difference? Why was 2006 any different?

Thankfully, with zoonoses, the reasons behind the outbreaks are relatively simple to grasp.

How Does Spillover Happen?

One of the most significant reasons that spillover happens is because of boons in the population of specific species of animals. This seems simple: if there are a lot of targets, something is going to get hit. Since viruses view living things as targets, the more white-tailed deer you have in an area, the more risk you have of viral spread.

So when you see charts like this from the Texas Landowners Association come out, you can see the potential for a virus to sweep through the animal population.

(This image isn’t common domain, so I’m not sure the appropriate means to cite it. Courtesy of Texas Landowners Association? Here’s the link.)

When this population increase happens, it also means that the animal has increased its range. You can only have so many field mice that can eat off five acres of land, so they will continue to spread out to adjacent acreage as their numbers increase. This, in turn, increases the number of animals those little field mice will come into contact with.

(Image courtesy of Jerzystrzelecki at Wikimedia Commons.)

A tick bites a deer and then bites a mouse. Then, the next day, the mouse eats something with a bit of horse poop. That little mouse will be exposed to more viruses the more creatures it comes into contact with. And like we've seen with Hendra in Australia, it's possible for something that impacts one little animal to then impact something else.

Hand in hand with all this, though, is confinement. Whether we're talking about human beings or animals, confinement/high population density is a problem regarding the disease. There's a reason that refugee populations are known for fiery outbreaks of measles, cholera, and tuberculosis. A virus doesn't have to travel far to find a host when everybody is all squished together.

The same can be said for population explosions of wildlife. When that happens, there will be animals that spread, but there will also be increased population densities, making it much easier for that animals to get sick.

(Image courtesy of Richard Bartz at Wikimedia Commons.)

This is part of the reason that confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs) have to keep such close tabs on regulating herd health. One sick cow can quickly lead to thousands of sick cows in a CAFO (all the more reason to farm like Joel Salatin).

And when you combine all of these factors – increased population size, increased population range, and increased species contact – you end up in a position where you're going to end up with increased human exposure to whatever those little viruses are that have been cooked up. The end result?

It could quickly end up being a spillover event.

David Quammen’s Warning?

(Image courtesy of Roda Viva at Wikimedia Commons.)

It isn't just the threat of a novel virus being created, however, that Quammen was concerned about. Sure, spillover events happen daily.

But what happens when you combine a spillover event with modern technology and the speed of travel? During the Black Death, when it was estimated that a third of Europe simply disappeared, the main ways that one traveled throughout Europe was either by ship or hoof. Voyages taking weeks to months were typical. And despite this, the plague decimated Europe.

What would happen if you added airplanes, cars, high-speed trains, metros, buses, and cruise ships? We can now travel faster than at any time before in history. What happens when we combine a novel spillover effect virus with a high fatality rate that is incredibly contagious with this travel speed?

(Image courtesy of Timemaps at Wikimedia Commons.)

It only takes a little imagination to see how this could quickly end up with the transportation of a global pandemic.

Consider the Following…

Researchers (genius ones, by the way) have discovered that zoonoses are somewhat predictable. We know that for X amount of new viruses we find in animals, a certain percentage of those novel viruses will be zoonoses. This can be determined by how many humans live near the animal, the host taxonomy, and the phylogenetic relatedness to humans.

This is excellent news. Knowledge is power, and if we know with a high degree of certainty that a select percentage of all the viruses we discover will have human infection potential, we can help determine how many "missing" spillover viruses are out there.

If I know that there are three zoonoses for every five chimp viruses, and I've found five chimp viruses that do not impact humans, then I know that there are three chimp viruses out there that do affect humans that I haven't seen yet.

Using this knowledge, researchers have mapped out where the missing spillover viruses are. We're "missing" viruses for bats in Central/South America, primates everywhere, rodents in North/South America/Africa, and carnivores in East/South Africa.

This is where we're at.

What Can We Do?

We have other tools at our disposal as well, though. You're about to witness the wonder of epidemiology.

Other researchers spent from 2009-2019 collecting over 75,000 wild animals, each with viral samples taken from it. Seven hundred twenty-one (!) new viruses were discovered in the process, and the researchers could use their findings to create an lgorithm-driven database known as the Spillover Tool.

This is an entirely open-source database where researchers can add information about new zoonoses they've discovered, and anybody can peruse to see what viruses have the highest pandemic potential.

To combat emerging infectious diseases, proper surveillance of infectious agents is paramount. If we have tools such as the Spillover Tool at our disposal, this helps researchers to keep tabs on emerging zoonotic threats.

For example, as Quammen chronicled in his book, for some time, people were dying from malaria infections that nobody could grasp. Several different parasites cause malaria, but these cases weren't responding to treatment as was hoped.

But virologists Balbir Singh and Janet-Cox Singh then made an important discovery. For years, people knew about Plasmodium knowlesi, a malaria parasite that targeted long-tailed and pig-tailed macaques. It had never impacted human beings before, so everybody getting sick was getting treatment for the typical human-associated malaria parasites. But they were being misdiagnosed. There had been a spillover event.

Plasmodium knowlesi (Image courtesy of Lyth O et al Wikimedia Commons)

What these people were actually dying from was P. knowlesi. They were dying from monkey malaria.

This is why it is so important for there to be virologists in the field who are monitoring and researching emerging viral threats. This is the importance of The Spillover Tool. Because when it comes to spillover, human lives are on the line.

What Can You Do?

From the individual's perspective, you can do three main things to prevent a spillover event: pest control, minimizing animal crowding, and wearing proper protection when working with animal poop/sick animals.

Pests such as ticks, bats, and mice can carry diseases. If you can keep their numbers in check and keep them out of your home, you can help minimize the risk they pose to you and your family. A clean house and other pest control techniques can help to mitigate this. For example, many people choose to raise guinea hens for the tick-eating benefits they provide. Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and alpha-gal are all thus prevented.

Guinea hen. (Image courtesy of eboy al Wikimedia Commons)

Secondly, if you have animals, ensure you're giving them plenty of space. A cat is a beautiful animal, but if your house is home to fifteen of them, you will create a viral breeding masterpiece. The same goes for farming. It can be tempting to pack as many cows into as small of a space as possible – and the farmer does have to be economical with his decisions – but you also have to consider the animal's health. This is one of the reasons that confined animal feeding operations aren't the best way to raise necessary meat protein. Intensive grazing and pasture management a la Joel Salatin are much better options, not only for happier food but for healthier food.

Swine CAFO. (Image courtesy of eboy al Wikimedia Commons)

Third, if you are working with sick animals or dung and urine, ensure you wear proper protection. Whether cleaning out animal stalls, dealing with a basement full of mice, or the like, you will want to protect yourself.

This is where MIRA Safety comes into play.

We sell a wide variety of gas masks, filters, HAZMAT suits, gloves, and more that will help keep you safe when exposed to biological threats. Our gear is so good that militaries worldwide rely on it to protect their troops from biological agents, and hospitals use us to protect against outbreaks. That alone should be convincing enough to also trust our gear.

Whether you're dealing with preventing a spillover event from happening in the first place or are trying to stay safe in the middle of an outbreak, MIRA Safety has you covered.

Spillover Woke People Up

David Quammen's book caused people worldwide to see the need to learn as much about zoonoses as possible. Book sales have spiked since 2020, and what Quammen said is incredibly relevant.