The word "Ebola" strikes fear into the hearts of millions across the globe. The term paints vivid images inside peoples' minds of bloody orifices, piles of corpses, and men in biohazard suits frantically running about. Add to this the repeated outbreaks of Ebola that the world has seen over the past 20 years, and yet more fuel is added to stoke the flames of fear.

But did you know that a particular strain of Ebola was first discovered in America? In fact, this was the first recorded outbreak of Ebola on American soil in history.>

Read on to learn more about the history of Reston Ebola.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

-

01

Outbreak #1

-

02

Global Spread of Reston Ebola

-

03

What Have We Learned About RESTV Since?

-

04

Advice for the Common Man

-

05

MIRA Safety Has You Covered

-

06

FAQs

Outbreak #1

In 1989, a small animal research laboratory outside Washington, DC, was about to make history. What was initially just another day at the Hazelton Research Products facility in Reston, Virginia, was soon to prove to be anything but. The lab was a well-respected location for animal testing - helping to ensure that various products were safe for use on human beings.

Reston, Virginia. (Image source: Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons )

They had just received yet another shipment of monkeys from the Philippines. They did not know, at the time, that the monkeys weren't the only thing that was shipped over.

One hundred macaques have shown up at the lab, where they have rapidly been moved over to the quarantine wing of the facility. This is a common step to ensure that no diseases accidentally brought over with the primates will cause any source of an outbreak for the other monkeys scattered throughout the building.

A macaque.

And as the macaques begin to show signs of illness, the staff is glad they've taken those precautions. At first, it was suspected that this was nothing more than a mild case of a common monkey bug called Simian virus (SV40) - something that can easily prove fatal to a monkey. Since a handful had already died, researchers had no reason to suspect otherwise.

Simian virus. (Image source: Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons )

But then, whatever it was that was killing monkeys exploded.

Monkeys within the quarantine wing began dying left and right, and this was happening at such a fast level that the staff quickly concluded that this wasn't Simian virus they were dealing with. This was something more - much more.

The telltale signs of hemorrhagic fever were unmistakable as monkey corpses piled up. The spleens were solid blood clots, and there were signs of bleeding within the gut. It was then that the staff realized they needed to take drastic action. That action came in the form of contacting the US Army. Specifically, the researchers reached out to USAMRID, the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases. They said that hemorrhagic fever was the fear, and as it turned out, this hunch proved correct.

Hemorrhagic fever during the Korean War. Note the lack of gloves. (Image source: Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons )

New Kid on the Block

During the 1980s, Ebola was new to the playing field for epidemiologists. Having just been discovered, very little was known about Ebola at the time. The cases that did pop up all happened in Africa, and given that these monkeys had all come from a monkey farm in the Philippines, it just didn't seem possible that Ebola could be the cause of all these deaths.

However, there are several different types of hemorrhagic fever, and as monkey corpses lay scattered about their cages, researchers rightly suspected that this was what they had on their hands. They hoped that wasn't the case, literally.

Ebola patient, 1976.

The thing about hemorrhagic fevers – especially ones that primates can catch – is that there is an excellent chance of their "spillover" into humans. This spillover is called zoonosis – a virus that starts in an animal before making the leap to humans. Nobody knew for sure, but there was a good chance that the entire staff at Hazelton Research Products had just contracted something that would lead to a miserable demise for each of them.

And given what was known about hemorrhagic fevers, there was a chance this wasn't limited to the lab. Hemorrhagic Fever could infect the human population of America as well.

Tom Geisberg was the scientist at USAMRIID tasked with identifying the samples coming out of the facility to determine what this outbreak could be. What he saw terrified him. This was Ebola. After several repeat tests to confirm what seemed impossible was true, Geisberg had confirmed beyond a shadow of a doubt that he had not made a mistake. These monkeys had died from one of the most lethal hemorrhagic fevers known to man. And those workers? They could be infected with it too.

From what Geisberg initially saw, it appeared as if this was the Zaire strain of Ebola – a strain known for having a 90% fatality rate in humans. And given that four workers from the laboratory had just tested positive for Ebola, things were looking bleak.

To add to the terror, everything seemed to indicate that the virus was airborne. Monkeys that weren't even in the quarantine wing began to grow ill and die with the same signs and symptoms. The facility was being ravaged.

Green Ebola virus attacks a (blue) kidney cell of a monkey. (Image source: Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons )

At the time, no policy or procedures for what to do with this type of outbreak on American soil existed. Everything was new, jerry-rigged, and ad hoc. And as a result, nobody knew what to do. Indecision was as pervasive as the Ebola virus was.

One of the first decisions was to euthanize the monkeys as quickly as possible. It was correctly assumed that they could efficiently serve as a transmission route to humans, amplifying the virus and disseminating it with terrifying ease if it was indeed airborne. Men entered the facility, pinning the monkeys with long poles before injecting them with a syringe containing the lethal cocktail that would eliminate them. When all was said and done, 450 monkeys had been euthanized.

But next, it had to be determined how the facility would be cleaned. The problem here was that this was right within a neighborhood. If Ebola was airborne, if it was spreading from room to room, perhaps through the HVAC system, something needed to be done now to ensure that it didn't float out of an open door.

The first step in preventing that from happening was to scrub everything. Bleach was used to clean down every surface so well that the paint was taken off the concrete floors. Electric frying pans were brought in and used to cook off formaldehyde crystals for three days to purify the air. After 11 days, the task was completed. The building was considered to be clean.

But despite all that had happened, what the researchers at USAMRIID discovered shocked them even more.

A Surprising Discovery

There are five strains of Ebola known to science at the moment. Every strain is lethal to humans – except for the one that had just broken out in Reston, Virginia – Reston Ebola. Though four workers had all shown positive tests for Ebola infections, not one of them ever got sick. For reasons still unknown to science, Reston Ebola is the only strain that behaves in this manner.

Ebola

Under the microscope, Reston Ebola is most similar to the Sudan strain of the virus – a strain that is known for leaving corpses in its wake. But for some reason that we still don’t understand, the one strain that popped up near Washington DC, of all places, didn’t cause human illness.

Perhaps even more shocking, however, is that only a few locals knew what was happening around them at the time. They saw men in hazmat suits, sure, but that didn't raise any alarms for anybody, and nobody seemed to care. That is until author Richard Preston released the story to the world in his seminal work The Hot Zone, which we've covered here at MIRA Safety in a previous blog.

But despite Preston's making Ebola a household name, the mystery of Reston Ebola lives on.

The fact is, we still need to learn more about it.

Global Spread of Reston Ebola

After that first outbreak in Virginia in 1989, it was in 1992-1993 that the next outbreak occurred in Sienna, Italy, traced back to the same Filipino monkey farm that had unintentionally caused the initial attack. In 1996, a third outbreak occurred again on American soil, this time in the great state of Texas.

At the Texas Primate Center in Alice, Texas, researchers noticed similar happenings as the 1989 outbreak. Subcutaneous bleeding, anorexia, bloody diarrhea – all found in the Texan monkeys.

But it wasn't until 2008 that the scientific world would be rocked again by Reston Ebola. For it was in this year that scientists found it in pigs.

At a swine farm in the Philippines, pigs started to grow ill with some strange disease. Upon closer inspection, scientists verified that this was indeed Ebola. By this point, scientists knew that pigs could replicate Zaire Ebola at very high levels within their lungs, serving as a potent source of human infection. We also learned that pigs could then easily give this Ebola to monkeys. So, while in hindsight, it may not seem that finding Reston Ebola within pigs should be that surprising, this was a first. We had no idea what we were dealing with.

To further complicate matters, it was discovered that one worker at the swine facility had tested positive for Reston Ebola as well. Fortunately, he never grew ill, but the fear existed that Reston Ebola may somehow be altered within the pig so that it could impact humans.

We'd seen about two dozen human cases of RESTV (Reston Ebola) by this point in history, none of which were symptomatic, but there was always the chance that this time could be different.

There were a few other outbreaks as well up to this point, but this was the first RESTV swine case we had seen up to this point.

What Have We Learned About RESTV Since?

While we've only seen clinically asymptomatic cases in humans, all of these cases have occurred in healthy adult males. If the victim were to be elderly, immunocompromised, female, or pregnant, we could see a different result.

Reston Ebola. Image courtesy of CSIRO (Image source: Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons )

We do know that even after the bloodstream is clear of the Ebola virus, there can still be infective transmissions that occur from breast milk, semen, vaginal fluid, or the eye for up to six months after the illness. Considering that we see this with lethal strains of Ebola, it is highly likely that this is the case for Reston Ebola. Of course, thankfully, there are some inherent differences with Reston Ebola compared to the other strains, but this is still a likely source of infection.

We also know that we probably don't have any clue as to how many human beings have been infected with RESTV. The only people ever tested for the infection are those who worked directly at the facilities where the outbreaks have occurred. If family members, friends, and others who had come into close contact with the infected were tested, we might discover that RESTV was much more infectious than we initially thought.

But again, thankfully, even when RESTV does infect somebody, it doesn't cause illness. At the moment, anyway.

We've since discovered Reston Ebola in other parts of the world, concluding that this is endemic to both the Philippines and China. Pigs in Shanghai have been caught with it, and it's thought that bats – known carriers of filoviruses, the type of virus that Ebola is – could easily carry RESTV as well. While science has concluded that Ebola is not an airborne infection and can only be spread through direct physical contact with infected material, it is postulated that pigs could potentially change this. The possibility that they cause aerosolized RESTV particles is a plausible current hypothesis.

Bat at a market in Africa. (Image source: Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons )

Spillover from animals to humans with viruses is always a risk, and because of this, researchers keep a very close eye on all things Reston Ebola. It's considered a biosafety Level 4 pathogen at the moment as a result of this.

But despite all of this, Reston Ebola has benefited humanity. Had it not been for the outbreak in Reston, Virginia, we would have never developed appropriate policies and procedures for the future lethal Ebola outbreaks that soon followed in Africa. Because of Reston Ebola, we were able to get healthcare workers over to Africa to help contain the epidemics that were tearing families apart and get those workers back here to the States without any loss of life or spread of the virus over here in America as well.

The Reston incident was more than scary, to be sure, but we learned from it and gleaned valuable lessons that helped us save lives not too far off in the future.

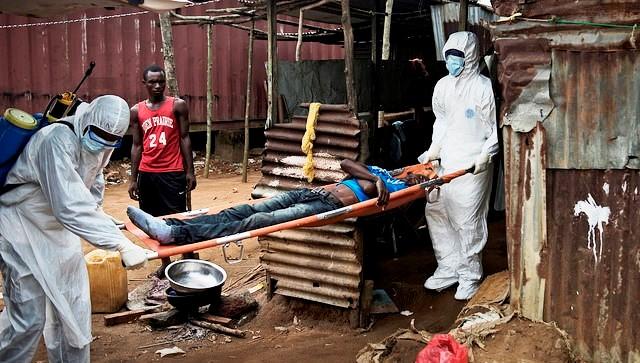

2014 Ebola outbreak.

From the individual, ordinary American person's standpoint, Reston Ebola isn't something you need to worry about. Realistically, Ebola on American soil isn't a threat you need to view as having a high probability of either. But that doesn't mean there aren't essential principles at work here. And those are things that you do need to consider.

Advice for the Common Man

The story of Reston Ebola hasn't just taught scientists several vital lessons. There are things of value that can be gleaned from this story, even for the average American.

For starters, spillover is a threat, and it's something that people need to take seriously. While you likely will never be placed in a situation where you have to worry about contracting Ebola when dealing with dirty or sick animal conditions, it is worth considering the use of proper protective equipment.

As we've noted before, if you're going to be cleaning out old, dirty barns, tending to sick livestock, or the like, you are at an increased risk of contracting zoonosis. This risk doesn't mean that you have to live in constant fear, nor that animals are a dangerous aspect of life that you should never come into contact with. Far from it.

This means that just like a lumberjack wears hearing and eye protection because of threats to his health that he knows are valid, so you should consider the same when dealing with actual probable threats. Keep in mind that the lumberjack isn't afraid of trees either.

He works with them daily. The same principle should apply to you with animals. Don't fear them, but consider that when spillover is a real potential risk (e.g., a homesteader working with sick waterfowl, natural reservoirs of influenza).

The second most significant lesson from RESTV we can learn is that there are surprises out there. Situations arise where proper respiratory protection and other PPE put away at your house could very easily help give you an "edge" when it comes to keeping your family alive and safe.

Poster found in Sierre Leone. (Image source: Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons )

MIRA Safety has you covered when dealing with these types of potential threats.

When dealing with potential spillover situations, at the very least, we recommend a quality pair of gloves and a proper respirator with a high-quality filter. We offer all of this and more.

For starters, consider our CM-6M gas mask. This mask will completely seal off your face from the outside environment, keeping anything potentially infectious from not only entering your lungs but from entering your body through your eyes as well. Of course, a gas mask is no good without a filter, and for these types of purposes, we recommend our NBC-77, a multi-purpose filter that will protect you against a wide variety of threats.

To keep your hands clean, we recommend our HAZ-GLOVES. These butyl rubber gloves are 129% thicker than the US Military standard, meaning there is minimal risk of tears or puncture wounds in these gloves, helping to keep your hands as protected from potential viral threats as possible.

Combined, these three pieces of gear will help minimize your risk of coming into contact with spillover-style agents. And if you find yourself working in a “hot zone,” we have additional gear, such as our butyl HAZMAT Overboots, HAZ-SUITs, and ChemTape that can keep you as protected as possible while outside of the laboratory.

So while RESTV doesn't need to be your concern, the lessons it taught us will be something you want to keep in mind. What are your thoughts on RESTV? Have you ever traveled to an area post-Ebola? Let us know in the comment section below.