The Historical Context of The Able Archer 83 Scare

In autumn of 1983, a Soviet pilot stands at the ready at his command post in East Germany. He is in the fighter-bomber division, and he and his comrades have just loaded nuclear bombs onto Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-23 jets. They have been ordered to man their posts round-the-clock, with preparations to “destroy first-line enemy targets” at a moment’s notice. Though our pilot is tired from his long shift, he takes heart in the fact that it is November 7: October Revolution Day.

Meanwhile, 19,000 American soldiers arrive in Europe, having been air-lifted across the Atlantic in radio silence. They taxi out of NATO hangars carrying what appears to be warheads. Communicating in a new format of coded messages, they prepare to release their own nuclear arsenal.

There’s just one small wrinkle: the American troops are practicing nuclear release procedures as part of an annual NATO military exercise. The warheads are realistic-looking dummies, and the new code was implemented to improve the security and efficiency of communication between NATO forces.

What is very real, however, is the situation of the Soviet pilot, whose government has mistakenly identified the NATO war game as a cover for a real attack. And so he–along with all units of the Soviet 4th Air Army in Poland–remain on high alert, and the fate of the world hangs in the balance.

But how did we get here? How did the world come to stand on the brink of oblivion over a simple miscommunication?

To answer that question, we must trace the history of the Cold War throughout the decades leading up to Able Archer 83–the formation of alliances, stockpiling of weapons, and even short-lived attempts at cooperation.

Featuring prominently in this series of events is nuclear weaponry: a technology that made it possible to kill thousands of people–millions, even–in the blink of an eye. With the stakes of conflict thus raised to this unprecedented level, the US and Soviet Union entered into a competition so intense, it could not be contained in this world: spilling out into outer space.

(Motorized launchers loaded with Lyulev 2K11 Krug surface-to-air missiles are paraded through Moscow's Red Square in 1967 )

Table of Contents

-

01

A Post-World War II Rivalry Begins

-

02

The Arms Race

-

03

NATO and the Warsaw Pact

-

04

The Space Race

-

05

Détente

-

06

A Breakdown of Relations

-

07

The Dramatic Leadup to Able Archer 83

-

08

Able Archer 83 Commences

-

09

Confusions Reign About Able Archer 83

-

10

The West’s Reaction

-

11

So, How Did This Happen?

-

12

Could It Happen Again?

-

13

What to Do in the Event of a Nuclear Strike?

-

14

Frequently Asked Questions

A Post-World War II Rivalry Begins

Prior to World War II, Great Britain loomed large on the world stage. With the most extensive colonial empire in history, it was a major economic and military power.

In the aftermath of the war, however, the balance of power shifted, and a new era of international relations began. From beneath the rubble of global catastrophe, two superpowers emerged: the United States and the Soviet Union.

(US Army and Red Army soldiers embrace on Elbe Day in 1945 (Wikipedia))

The two nations had been allies in the fight against Nazi Germany, but with the defeat of the Axis powers, their alliance was quickly replaced by a rivalry that would define geopolitics for decades to come.

This rivalry came to be known as the Cold War. Rather than meeting on the field of battle (directly, anyway), the major players of the Cold War fought along political and ideological lines, using a variety of means, such as propaganda, espionage, and proxy wars.

At its core, the Cold War was a battle for global dominance between two very different systems of government and economics, with Western capitalism on one side, and Eastern communism on the other. Adding a new layer of horror to the clash was the fact that both sides were armed with nuclear weapons–and inclined to use them if provoked.

The conflict officially began in 1947 with the introduction of the Truman Doctrine, wherein the US pledged to provide military and economic aid to any country threatened by communism.

In response, the Soviet Union launched its own aid program, the Molotov Plan, which provided economic assistance to countries in the Soviet sphere of influence in order to counter the threat of US imperialism.

It was in this way that the two nations entered into a decades-long period of intense competition, with the specter of nuclear war weighing heavily on the minds of Americans and Soviet citizens alike.

(Bygone days: Allied leaders (Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin) meet at the Yalta Conference in the Soviet Union in February 1945)

The Arms Race

In 1949, a Soviet scientist, looking over a remote expanse of grassland plains in northeast Kazakhstan, witnessed something that no Russian had seen before:

"On top of the tower an unbearably bright light blazed up. For a moment or so it dimmed and then with new force began to grow quickly. The white fireball engulfed the tower and the workshop and, expanding rapidly, changing color, it rushed upwards… The fireball, rising and revolving, turned orange, red. Then dark streaks appeared. Streams of dust, fragments of brick and board were drawn in after it, as into a funnel."

(The Soviet Union’s first atomic bomb test at Semipalatinsk Test Site, Kazakhstan (PBS))

Just four years earlier, the US had secured the unconditional surrender of Japan, and drawn World War II to a close, by dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Now, the Soviet Union had tested its first atomic bomb, and the nuclear arms race began.

The United States responded to the Soviet atomic test with a massive expansion of its own nuclear arsenal, and the two nations entered into a dangerous cycle of nuclear brinkmanship. As tensions escalated, both sides continued to build and test increasingly powerful weapons, including intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear warheads anywhere in the world.

NATO and the Warsaw Pact

Of course, no war can be won by dint of nuclear weapons alone. Sometimes, you need a little help from your friends.

As the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in their arms race, they also began to form alliances with other nations. In 1949, the US, Canada, and ten Western European nations formed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a mutual defense pact designed to deter Soviet expansionism.

The Soviet Union responded with the creation of the Warsaw Pact, a defense treaty signed by the Soviet Union and members of its Eastern Bloc. With the Warsaw Pact serving as a counterbalance to NATO, the two alliances faced off against each other in a tense and dangerous standoff that lasted for decades.

(Image courtesy of (Britannica))

The Space Race

Roughly 65 years ago, a compact, reflective sphere made of highly polished aluminum alloy, with four long antennas extending from its body, receded into the night sky of Kazakhstan: a small bright light. From there, it streaked westward, passing over Jerusalem, the Sahara desert, the southern Atlantic ocean, Antarctica, and Mexico.

Then, it moved over the United States, where observers in Houston looked on in horror. Though the 23-inch object could do little more than emit a “beep beep” sound–heard by ham radio enthusiasts around the world–its symbolic value was immense.

"[The Soviets] must not be allowed to win this game,” American rocketeers in the scholarly journal, Astronautics, insisted, “a game with far-reaching political, social and economic consequences.”

(Image courtesy of (Barnebys))

The 1957 launch of Sputnik I, the world’s first artificial satellite, inaugurated the beginning of the Space Race. A major propaganda victory for the Soviet Union, the tiny object initiated a shift in American attitudes towards the technological capabilities–and military might–of their Eastern rival.

On one hand, the R-7 missile that had (in modified form) launched Sputnik I into space represented scientific progress, but, on the other, it grimly foretold the capability of the Soviet Union to launch a nuclear warhead into US airspace.

These fears were crystallized in numerous contemporaneous publications, including an English editorial called “Next stop Mars?”. Acknowledging that the achievement of Soviet technicians is “immense,” it nevertheless laments, “If Mars is still distant, what of Russia’s war capacity on Earth? There little doubt can remain. The Russians can now build ballistic missiles capable of hitting any chosen target anywhere in the world.”

Amid fears of a “technological gap” between the US and Soviet Union, the American government responded to the launch of Sputnik I with a massive investment in space technology, including the creation of NASA and a concerted effort to send a man to the moon. Running parallel to this was increased intelligence gathering of Soviet military activities, including the CORONA program, the nation's first imaging reconnaissance satellites.

((A Soviet technician gives Sputnik some TLC (Sovfoto / Getty Images))

Détente

In 1972, Richard Nixon visited the Soviet Union for the first time as president. He had been there three times before–most notably, in 1959, as vice-president.

During this visit, Nixon had made headlines for engaging in an impromptu “kitchen debate” with Nikita Khrushchev, then the Soviet Premier. These exchanges took place at the opening of the American National Exhibition in Moscow, which was, according to an American newsreader, “dedicated to showcasing the highest standard of life in our country.”

(The titular kitchen from Nixon and Khrushchev’s infamous 1959 “kitchen debate” (Politico))

There, a conversation about kitchen appliances had sparked a duel of words between Nixon and Khrushchev, beginning in a model of a suburban American house, and then continuing on camera during a joint press conference. In response to a reporter, the Soviet premier had harshly criticized the exhibition for “not [being] in order,” and then vowed to economically overtake the United States within seven years.

After that, he turned to Nixon and quipped: “As we pass you by, we’ll wave ‘hi’ to you, and if you want, we’ll stop and say, ‘Please come along behind us.’”

As Khrushchev chuckled and waved sardonically, Nixon smiled politely, no doubt through gritted teeth.

When it was his turn to speak, he countered: “If this competition is to do the best for our people… there must be a free exchange of ideas. There are some instances where you may be ahead of us–for example in the development of your rockets, for the investigation of outer space. There may be some instances–for example, color television–where we’re ahead of you. But, in order for both of us–”

Here, Khrushchev cut Nixon off, waving his hand dismissively. “No, in rockets we’ve passed you by, and in technology…”

Nixon, visibly repressing frustration, doubled down. “Here you can see the type of tape which will transmit this very conversation immediately,” he said, motioning to the camera. “This indicates the possibility of increasing communication and this increased communication will teach us some things, and it will teach you some things too.”

Patting Khrushchev with his extended index finger, he added, “Because, after all, you don’t know everything.”

(IYou don’t know everything”: Nixon offers Khrushchev strong words (Wikipedia))

At the time, Nixon’s “kitchen debate” had considerably boosted his popularity, earning him praise for his ability to hold his own against the bombastic–yet formidable–Khrushchev. As The New York Times noted in 1972, however, “the contrast between Nixon '59 and Nixon '72 was striking in the way he dealt… with Soviet leaders.”

Facing off against General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, Nixon was said to be more “relaxed” and “taking a longer view.” He even, at the first plenary session of the Communist Party, made the famously “dour” Soviet premier, Aleksey Kosygin, smile for the first time that day.

Likewise, Nixon’s approach to the Soviet people was markedly different. While his 1959 speech was considered to be a master class in “refutational rhetoric,” his 1972 speech was “an effort to reach and stir the emotions of millions of Soviet citizens,” littered with references to Russian culture.

In describing the sun-showers that greeted him upon arrival in the Soviet Union, for example, Nixon had used the Russian term “mushroom rain,” or mushroom-gathering weather, widely considered by Russians to be a good omen.

With time, the reportedly relaxed mood of Nixon’s 1972 visit to Moscow came to be known as “détente,” or an easing of hostility between the United States and Soviet Union. This period of relative calm was marked by a series of agreements aimed at arms control, including the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM). The treaties sought to limit the number of nuclear weapons possessed by both nations and to create a more stable and peaceful international environment.

There was even a joint space mission between the US and Soviet Union, the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project.

(A tender moment of détente: Cosmonaut Alexey Leonov (left) and astronaut Deke Slayton (right) pal around during the joint Apollo–Soyuz linkup in July 1975. (NASA Human Space Flight Gallery))

In spite of these positive developments, however, the era of détente came to an unceremonious end in 1979, with several events that year acting as a catalyst, such as the Soviet Union’s intervention in Afghanistan, as well as NATO deploying a new set of upgraded missiles in Europe.

Notably, more than 100 of these missiles were "Pershing II" medium-range missiles, placed in West Germany and aimed East. In order to avoid violating the SALT II arms reduction treaty, signed between U.S. president Jimmy Carter and Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev earlier in the year, which restricted the US’ ability to build new missile launch sites, the missiles were retrofitted into Pershing 1a launch sites.

Needless to say, Brezhnev was not amused by this loophole–a reaction anticipated by NATO. In fact, they had hoped to ruffle his feathers.

A couple of years prior, the organization had been enraged by the Soviet Union’s decision to deploy SS-20 “Saber” missiles along the Iron Curtain. NATO hoped that, by situating the “Pershing II” missiles opposite their Eastern counterparts, they would drive home the danger of mutually assured destruction, and Soviet officials would agree to enter into arms control negotiations. This strategy was employed as a part of NATO’s “double track decision,” which offered the Warsaw Pact a mutual limitation of medium-range ballistic missiles, whilst also threatening to install more if they refused to negotiate.

The plan didn’t work, and the last vestiges of détente evaporated like Nixon’s “mushroom rain.”

(ISS-20 “Saber” missile–called RSD-10 Pioneer in the Soviet Union–and launcher on display in Kiev (Wikipedia))

A Breakdown of Relations

In 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev reflected: “Never, perhaps, in the postwar decades has the situation in the world been as explosive and, hence, more difficult and unfavorable as in the first half of the 1980's.”

To be sure, the early 1980s was a period of intense tension in the relations between the two superpowers, as the previous decade’s détente gave way to a reignited clash between the superpowers.

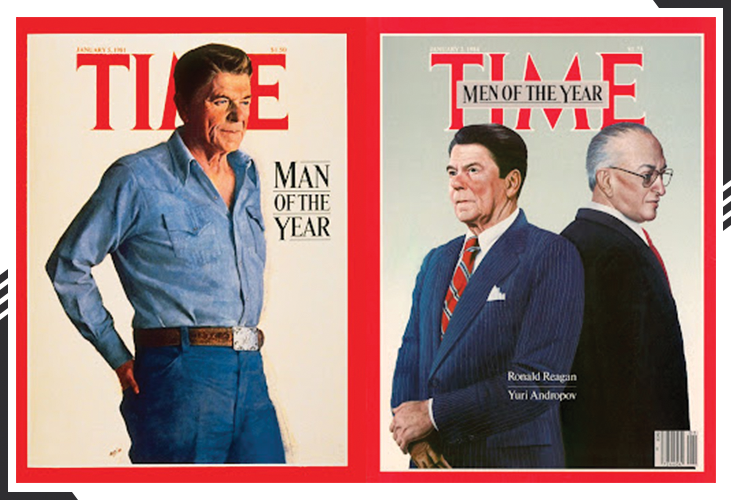

(Reagan as Time’s “Man of the Year” in 1981, a title he shared in 1984 with Yuri Andropov (Time))

This was, in part, due to a change in leadership on both sides. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan came to power, having promised to pursue a more assertive foreign policy that would contain Soviet expansionism and support anti-Soviet forces around the world. During his presidency, the defense budget doubled.

Meanwhile, Yuri Andropov succeeded Brezhnev as General Secretary the following year. Like Reagan, Andropov was a hardliner who believed in maintaining a strong military posture. And while his American adversary pursued a major buildup of military forces, Andropov presided over a major expansion of Soviet intelligence operations aimed at the United States and its allies.

As a matter of fact, Andropov had, whilst heading the KGB the previous year, launched the intelligence program Operation RYaN. The operation’s name was an acronym describing a sudden nuclear attack, and the objective was to detect enemy military preparations for a nuclear strike.

Andropov, who was said to suffer from a “Hungarian complex”–or a deep mistrust of dissent and opposition–believed that the United States was preparing for a nuclear first strike against the Soviet Union and that Operation RYaN would provide the necessary intelligence to counter such a calamity.

These fears were further fueled by Reagan's proposed missile defense system, the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), mockingly dubbed "Star Wars" in the press.

According to the US Department of State, “The heart of the SDI program was a plan to develop a space-based missile defense program that could protect the country from a large-scale nuclear attack.” It was “dependent on futuristic technology, including space-based laser systems that had not yet been developed, although the idea had been portrayed as real in science fiction.”

As the US poured billions into its development, critics decried the program as an expensive, infeasible bit of sci-fi schlock.

For the Soviet Union, however, the “Star Wars” program was no space opera. Instead, it was viewed as a means of gaining a strategic advantage in a potential conflict, in spite of Reagan’s insistence that the system was purely defensive.

(President Reagan announcing the Strategic Defense Initiative in 1983 (The Heritage Foundation))

The Dramatic Leadup to Able Archer 83

In 1983, tensions continued to escalate. On the American side, Reagan famously called the Soviet Union "an evil empire" in March of that year.

His speech drew an angry reaction from Andropov, who warned, “The incumbent US administration continues to tread an extremely perilous path… It is time they stopped devising one option after another in the search of the best ways of unleashing nuclear war in the hope of winning it. Engaging in this is not just irresponsible, it is insane.”

In September of the same year, Korean Airlines Flight 007, a civilian airliner flying from Anchorage to Seoul, deviated from its intended course. The Soviet Union, thinking that the plane was a military aircraft, shot it down, resulting in the deaths of all 269 passengers on board, including Larry McDonald, a congressman known for his stalwart anti-communist views.

In a speech to the nation on September 5, 1983, Reagan said: "The Soviet Union's actions against the Korean airliner constitute one of the most serious incidents between our two countries. It is a shocking and appalling act, one that must not go unanswered."

Able Archer 83 Commences

It was against this backdrop that Able Archer 83, an annual NATO military exercise, was held from November 7 to 11, 1983.

(NATO troops from a battalion based in Fort Hood, Texas train in Germany in September 1983, two months before the events of Able Archer 83. (Photo by John van Hasselt / Sygma via Getty Images))

The premise of the war game was as follows: the simulated mayhem would start with a change in Soviet leadership (to a more staunchly anti-West leader), then progress to heightened proxy rivalries in the Gulf States and Eastern Europe. After that, a Warsaw Pact invasion of Yugoslavia, Norway, Germany, and Greece would ensue, culminating in NATO deploying nuclear weapons as a last resort.

In this way, NATO would test their ability to respond to a Soviet nuclear attack, as well as practice the procedures for launching a retaliatory strike.

It was meant to simulate these conditions realistically–more realistically, indeed, than in previous years.

This heightened realism proved too effective, however, as the Soviet Union feared that the war game was a pretext for a real first strike.

You see, Soviet leaders were already on edge for previously mentioned reasons, such as the Strategic Defense Initiative and recent deployment of Pershing II missiles in Europe.

With respect to the latter, Soviet officials had miscalculated the missiles’ range, believing them capable of striking Moscow with little to no warning. KGB documents from 1983 confirm this misapprehension: “The so-called period of anticipation essential for the Soviet Union to take retaliatory measures…will be considerably curtailed after the deployment of the ‘Pershing-2’ missiles in the FRG, for which the flying time to reach long-range targets in the Soviet Union is calculated at four to six minutes.”

For all of these reasons, the Soviet Union came to believe that the United States was preparing for a nuclear war, and that the exercise could well be a cover for a surprise attack.

Tanks crossing a bridge during the war game

Confusions Reign About Able Archer 83

What is perhaps most surprising about a war game bringing the world to the brink of nuclear war is the fact that the West was largely oblivious to their near brush with Armageddon, only later realizing the full extent of the danger of the Able Archer 83 scare.

Prior to this revelation, prevailing wisdom among American officials held that the Able Archer 83 exercise was so “routine” that there was no cause for serious concern among the Soviet Union’s top brass.

As the recently declassified President’s Foreign Intelligence Review Board (PFIAB) report puts it: “We noticed a tendency for most to describe the annual Able Archer exercise simply as a ‘command and control exercise’ and thus, clearly nonthreatening to the Warsaw Pact.”

As the 1990 report goes on to note, however, there were in fact several unique, never-before-seen features of the war game. These included a radio-silent air lift of 19,000 US soldiers to Europe, the shifting of commands to an alternate war headquarters, the practice of new nuclear weapons release procedures, and several inadvertent references to B-52 sorties as nuclear "strikes."

There were other “special wrinkles,” as the PFIAB report puts it, too. For instance, the 1983 version of Able Archer moved forces through all alert phases, from DEFCON 5 to DEFCON 1, rather than remaining at General Alert throughout, as in previous exercises. Plus, the simulation took on newfound realism when aircrafts practiced warhead handling procedures with authentic-looking dummy warheads.

(Image courtesy of (NSA Archive) A slide from the Wintex-Cimex 83 exercise illustrates the US alert system)

Seen through the lens of Cold War mistrust and paranoia, these anomalies more closely resembled harbingers of doom than the trappings of a routine “command and control exercise.”

In fact, a Moscow Center memo from two days before the exercise advised agents to closely monitor “changes in the method of operating communications systems and the level of manning,” as new NATO procedures “may… indicate the state of preparation for RYaN,” i.e., a nuclear missile attack.

When Able Archer 83 commenced, and Soviet assets observed that NATO was indeed implementing new, unprecedented procedures, as well as a new format of coded communication, their hypothesized indicators of an impending attack appeared to be corroborated.

Consequently, the Soviet Union put fighter-bombers loaded with nuclear bombs on 24-hour alert in East Germany, with preparations for the immediate use of said weapons.

(Image courtesy of KGB Annual Report for 1981 (Wilson Center Digital Archive))

The West’s Reaction

As the Soviets’ finger hovered over the proverbial big red button, the US remained mostly in the dark. The PFIAB report explains:

“This abnormal Soviet behavior to the annual, announced Able Archer 83 exercise sounded no alarm bells in the US Indications and Warning system. United States commanders on the scene were not aware of any pronounced superpower tension, and the Soviet activities were not seen in their totality until long after the exercise was over. For example, while the US detected a ‘heightened readiness’ among some Soviet Air Force divisions, the extent of the alert… was not known until two weeks had passed after the completion of the exercise. The Soviet Air Force stand down had been in effect for nearly a week before fully armed MIG-23 aircraft were noted on air defense alert in East Germany.”

The report goes on to explain that the US intelligence community deemed the Soviet military response to Able Archer 83 to be “unusual but not militarily significant.” After all, “more indicators should have been detected if the Soviets were seriously concerned about a NATO attack.”

What’s more, this perception persisted for years, with the report admitting: “The US intelligence community did not at the time, and for several years afterwards, attach sufficient weight to the possibility that the war scare was real. As a result, the President was given assessments of Soviet attitudes and actions that understated the risks to the United States.”

It was not until 1985, when KGB rezident and British intelligence asset Oleg Gordievsky defected to the UK, that the true magnitude of the Able Archer 83 scare was appreciated. At the time of the exercise, Gordievsky, a double agent, had been feeding information to British intelligence, but American officers had dismissed Gordievsky’s claims as Soviet propaganda, unsupported by any “hard evidence.”

It would not be until the next decade, in 1990, that American officials acknowledged they had been wrong, concluding: “In 1983, we may have inadvertently placed our relations with the Soviet Union on a hair trigger.”

(Image courtesy of The Spectator) Oleg Gordievsky, a KGB agent who became disillusioned with the Soviet government)

So, How Did This Happen?

There are, of course, plenty of events that directly contributed to the near-disaster that was the Able Archer 83 scare, and several of them have already been mentioned.

With that said, it may be more useful to take a macro approach to one’s analysis. Looking back on the decades that preceded the 1983 exercise, it is clear that the relationship between the United States and Soviet Union was one of profound mistrust, bitter rivalry, and fierce opposition to the other’s belief systems. Both were armed to the teeth, and deeply afraid of a nuclear attack.

Even in the détente years, the relationship between the superpowers was, at best, an unhappy marriage between two parties that had been brought together not by love, but geopolitical happenstance. And as is wont to happen in unhappy marriages, the two eventually resumed quarreling.

(No love lost: Americans celebrate the death of Stalin (Getty Images))

Could It Happen Again?

Though the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, and its successor, the Russian Federation, is considered a “great power” rather than a “superpower,” the rivalry between East and West continues. Except, this time, the former is headed by a strategic partnership between Russia and China.

Military exercises, too, remain a persistent cause of anxiety between feuding nations the world over.

In early April of 2023, for example, the president of Taiwan, Tsai Ing-wen, met with the US house speaker in Los Angeles, drawing an angry reaction from China. The country responded by deploying naval assets to Taiwanese waters, simulating missile attacks and practicing ship-launched strikes on Taiwan.

President Tsai condemned the three-day war game, saying that the drills were irresponsible and caused instability in Taiwan.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken echoed her assessment, saying: “Beijing should not use the transits as an excuse to take any actions, to ratchet up tensions, to further push at changing the status quo.”

Soon after, the US and Philippines held exercises of their own across the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait, which, according to Sky News, is “likely to further inflame tensions with China."

The joint operation, though planned, constituted the countries’ largest combat drills in decades.

(Rocket launchers firing on a snowy field during joint exercises with Belarus in February 2020 (Handout/Russian defense ministry/AFP))

Even more notable were the Russian and Belarusian military exercises in the Black Sea in February of 2022. At the time, numerous publications raised concerns that the joint naval maneuvers were a “possible route for Russian troops to invade Ukraine.”

Meanwhile, Ukraine responded with exercises of their own, and President Joe Biden warned Americans in Ukraine to leave as soon as possible, as an invasion may be imminent.

Days later, international concerns about the exercises proved well-founded when Russia invaded Ukraine.

Where this leaves us, then, is a world where military drills can be a source of worry, as in the Taiwan Strait–or a genuine sign of an imminent attack, as in the case of Russia and Ukraine.

Given the fact that nine nations now possess nuclear weapons, this ambiguity is more than a little unsettling–yet unlikely to resolve anytime soon.

What to Do in the Event of a Nuclear Strike?

So, what should you do if the worst should happen?

Well, if this story has taught us anything, it should be not to panic. Instead, take practical steps to prepare yourself. That way, you can rest assured that you and your family will be safe during an emergency.

If you don’t know where to start, consult this list of the top nine products to start–or add to–your personal protective equipment (PPE) kit.

Did you know that the Chernobyl meltdown registered high levels of radiation all the way in Sweden? As a matter of fact, the early detection system at Sweden’s Forsmark power plant–hundreds of miles away from Ukraine–played a crucial role in pressuring the Soviet Union to open up about the disaster on the global stage.

The fact that, to this day, Swedish and Norwegian farmers are affected by the legacy of Chernobyl’s radioactivity teaches us a valuable lesson: fallout has no borders.

That’s why it’s a good idea to stock up on potassium iodine tablets, whether you’re located in North America, Europe, or elsewhere. These potentially life-saving tablets work by flooding your thyroid glands with safe iodine. Take them at the first sign of a nuclear event–whether near or far–and they will protect you from absorbing potentially fatal I-131 isotopes that can be dispersed into the atmosphere following a blast.

Note that potassium iodide is also available in MIRA Safety's nuclear survival kit, which also includes a NBC-77 filter, canteen, leg-mounted pouch, and full-face respirator. If you are new to PPE, this kit takes the guesswork out of the must-need basics.

And for the littles in your family, be sure to check out the children's version, which features the new MD-1 Children’s Gas Mask: the only reusable gas mask designed specifically for children that can be found in today's market.

As the far-reaching consequences of Chernobyl shows us, radiation can travel far, and last a long time. It’s important to protect yourself from such exposure, whether following a nuclear blast, or in everyday life.

For those not stationed at a power plant, however, you’ll need a device to monitor and measure radioactive pollution. Small, customizable, and rechargeable, the Geiger-2 is the perfect dosimeter for civilians who are concerned about their health.

Potassium iodine tablets are your first line of defense against radiation. But depending on your proximity to a potential blast, you may have to leave your home for an extended period of time. To ensure preparedness for such an eventuality, it would be prudent to consider acquiring hazmat gear such as MIRA Safety's CM-6M, which features a full-face respirator. The combined mask and respirator protects your face, internal organs, and respiratory system against a wide spectrum of chemical warfare agents, including radioactive dust.

For comprehensive protection, this mask can be paired with Kappler chemtape, durable chemical-resistant gloves, overboots, and a protective HAZMAT suit.

This mask can be purchased separately or as a part of MIRA Safety's nuclear survival kit.

Once you’ve got your gas mask, you’ll need a filter. Filter use time depends on a few different factors, including atmospheric conditions, contaminant type, concentration, as well as your breathing rate. As a general guideline, however, we would recommend having two filters per person per day, in the event of an emergency evacuation scenario.

(As a reminder, this filter is also available as an essential part of MIRA Safety's foolproof nuclear survival kit.)

5. MB-90 Powered Air Purifying Respirator

For many readers, the filter above will suffice. However, for those with respiratory problems, or anyone who lacks the lung capacity to inflate a large balloon, a standard gas mask, including the one above, will be unsuitable. That’s because filters increase breathing resistance, and not everyone has the lung power to draw in air through a filter.

So if you have family members who are young, elderly, or chronically ill, you may want to consider investing in an air purifying respirator. This detachable unit, based on a design from the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), reduces the weight of the mask, making it easier to maneuver. As such, the wearer will find it easier to both breathe and move–a valuable upgrade for your most vulnerable family members.

6. HAZ-SUIT® Protective CBRN HAZMAT Suit

Now that your gas mask and filter is sorted, you’ll need a hazmat suit. This MIRA Safety suit, which is durable and long-lasting, adds a crucial layer of protection against alpha and beta rays. Note that it will not insulate you from gamma waves–in that case, the only thing that can protect you is time, distance, and shielding.

With that said, the fabric is rated to protect wearers against chemical warfare agents.

7. NC-11 Protective CBRN Gloves

Next, you’ll need these gloves, which provide up to twenty-four hours of protection against nuclear threats–as well as biological and chemical ones. This will buy you enough time to get out of immediate danger and seek shelter elsewhere.

With proven performance under even the most extreme conditions, these gloves are a necessary addition to any PPE kit worth its salt.

8. Combat CBRN Overboots Model S

Made to fit over the combat boots you’ve already got in your closet, MIRA Safety’s Combat CBRN Overboots add a layer of protection from nuclear fallout. With a ten-year shelf life, these overboots will stand the test of time, remaining in good condition for when you need them most. And because you will likely be in a hurry–not to mention wearing thick gloves–in such an event, they are designed to be easily put on and off.

Light and flexible, these overboots will not slow you down, but they will help to keep you safe, making them well-worth including in your PPE kit.

9. Kappler ChemTape Chemical Resistant Tape

Though it may not be the most eye-catching part of a PPE kit, chemical resistant tape is nevertheless an absolute must for protection against hazardous chemicals, providing critical reinforcement by sealing the gaps where your hazmat suit meets your gloves, boots, and the edge of your respirator/gas mask. With a potentially unlimited shelf life, there’s no reason not to keep this tape in your supplies.